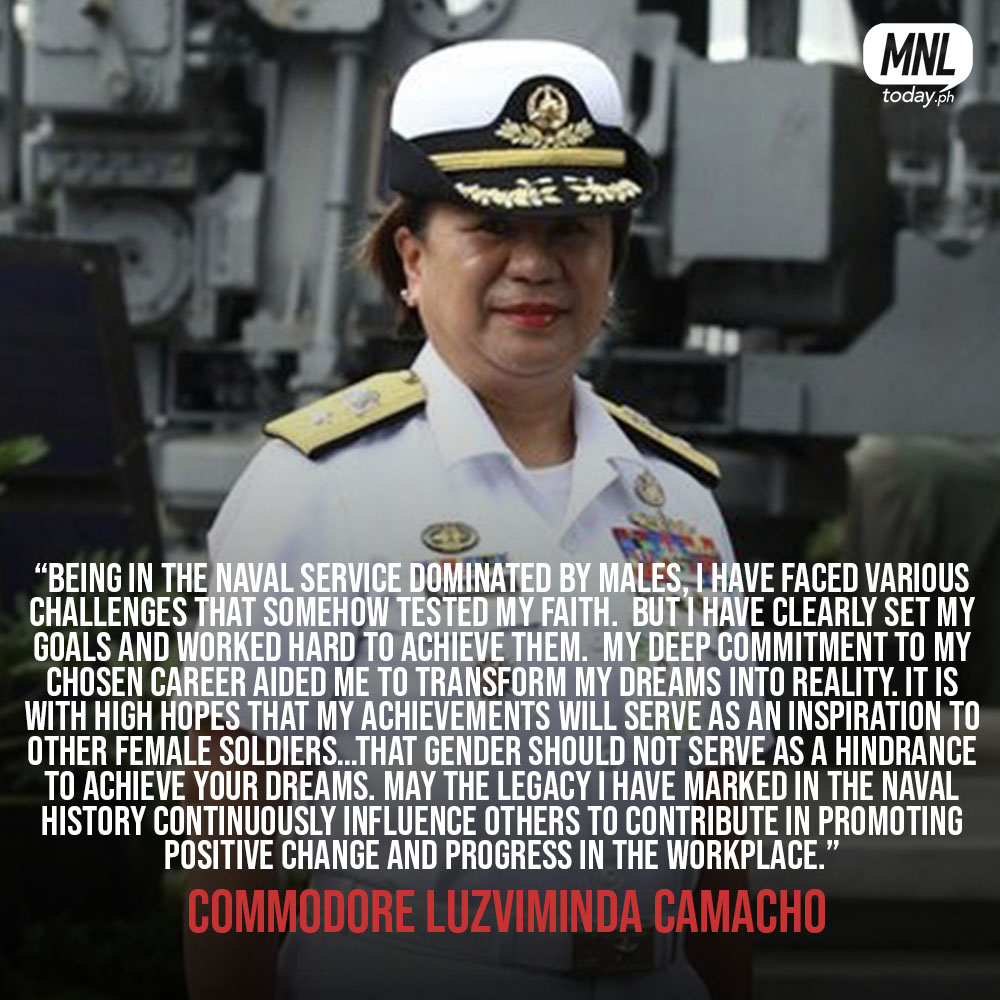

In an industry or profession dominated by men, it is likely that a woman who rises to the occasion will stand out.

Commodore is a senior naval rank used in many navies which is equivalent to Brigadier and Air Commodore that is superior to a navy captain, but below a rear admiral. And that is “Ma’am Commodore” Luzviminda Camacho to her peers in the Philippine Navy.

In 1987, her father – then a chief petty officer in the Navy encouraged Commodore Luzviminda Camacho to join the military. It seems to be fate because from that time on, she has never regretted his advice.

“My father was the one who encouraged me to join the Navy. At that time, I just graduated with an Industrial Engineering degree from Adamson University and was already working as a quality control officer in an electronics company in FTI (in Taguig City), I was the eldest of five siblings,” shared Camacho.

So take the exams she did and she shortly found herself undergoing grueling physical training at the Armed Forces Training Command at Tanay, Rizal as a candidate soldier under the Women’s Auxiliary Corps (WAC) for three months.

After that, she proceeded to the next stage of her training at the Naval Education and Training Command in Fort San Felipe in Cavite City in December 1988, graduating in February the following year. That March, she reported for work at the Navy headquarters on Roxas Boulevard.

Camacho has achieved many firsts in the Navy: She became the first female skipper or commanding officer of a Navy ship; the first female commander of a Philippine contingent to a United Nations peacekeeping force and the first female star-ranked naval officer.

Currently, she is chief of the Armed Forces’ Office of Legislative Affairs in Camp Aguinaldo.

It was hardworking and determination as Commodore Camacho had to prove herself and worth in the Philippine Navy. In her first years, her work was mostly administrative and secretarial. Since that time, women in the military were uncommon and not assigned combat duties under the WAC.

She felt that as a college graduate, there was more that the military could offer, and more that she could contribute to the service. So she applied to the Officer Candidate School of the Armed Forces and found herself and her gear back in Tanay in October 1989. She graduated in August 1990 as a lieutenant. Since she also trained with the Navy, she asked to be assigned back to headquarters where she was made an adjutant.

In the following years, she continued to be promoted and took more courses to obtain senior posts, but she still wanted to be organic or to be a line officer with the Navy, and not just under the WAC. Thanks to Republic Act 7192, which expanded the role of women in nation building, she got her wish.

To be a lieutenant commander, an officer is required to be “aboard ship” – equivalent to being in an infantry unit in the Army – so she was posted as an executive officer or “Ex-O” of BRP Cebu (PS 28), a 56-meter corvette that was constantly on offshore patrol off the coast of the Bicol region. It was on this assignment in 2007 that she faced one of the most difficult challenges in her naval career.

“As an Ex-O, your primary responsibility is the morale and discipline of your men,” Camacho explains. She declined to give details of the infractions she did not let pass but recalls she was “challenged” by her subordinates as well as her superiors of the Offshore Combat Force to which her ship belonged.

“They (erring crew) thought they could influence me but I was there to implement the regulations, any violator must face punishment, there’s always a delinquency report,” she said.

“When you’re on mission there must be teamwork, and efficiency,” she adds.

Camacho recalls that when she was a skipper of another patrol ship, some crew members violated or abused their R&R (rest and recreation) privileges. Once “taps” are sounded at 10 p.m., all crew must be back from their R&R and she took possession of the liberty log book to make sure that those who were tardy would not go unnoticed.

Not surprisingly, the discipline made her subordinates “grow” as the regulations are made clear to them and the punishments are explained, she says.

Being a woman was an advantage when she was assigned as the deputy of the Office of Ethical Standards and Public Accountability (OESPA) where she dealt with various personnel problems, including when military duties and personal obligations cross and conflict.

At the OESPA, she had to tackle family problems of naval personnel as well as cases of sexual harassment.“Victims often confide and speak up when they talk to a female officer,” Camacho admits.

In 2013, she became the first female commander of the Philippine military contingent to the UN Stabilization Mission in Haiti (MINUSTAH) composed of 11 navy officers and 145 sailors and marines. Subsequently, she was tasked as commander of the Joint Task Group Liberia that spearheaded the successful transportation, quarantine and post quarantine of the 142 members of the 18th Philippine Contingent to Liberia. In Haiti, the Philippine contingent had the difficult responsibility of providing administrative and security services to UN personnel.

In March 2011, she pursued graduate studies, earning the degree of Masters in Public Management Major in Development and Security at the Development Academy of the Philippines.

Camacho dedicates all her achievements and service to her only son, Praise Bisleg, who is now abroad after finishing his Bachelor of Science in Marine Transportation at the Maritime Academy of Asia and the Pacific in May 2014.

NOTE: THIS IS AN EXCERPT FROM Philippine Star’s STARweek feature article, written by Paolo Romero, published last March 8,2020.

Photo courtesy: Armed Forces of the Philippines, Philstar Global, Abs-Cbn News